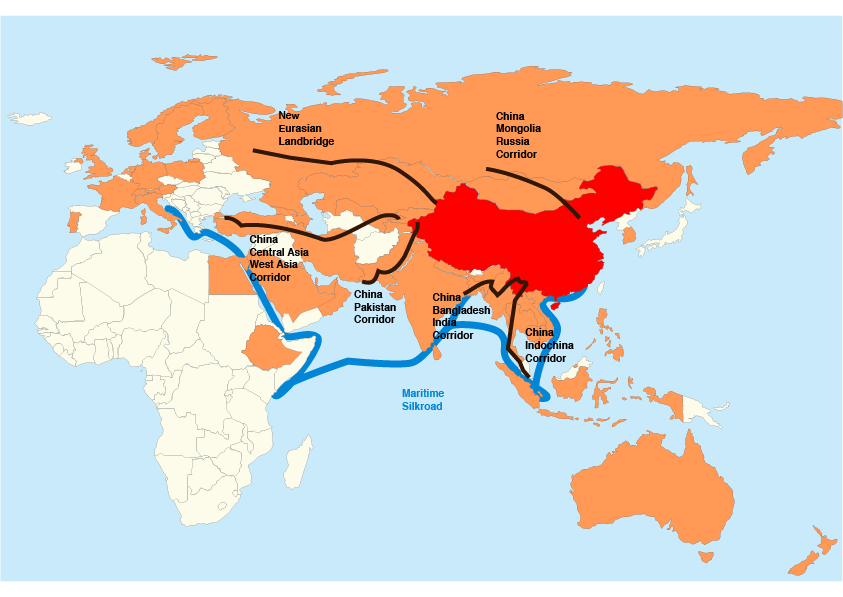

China’s foreign influence has grown significantly over the recent years. Quite a few observers speculate the country might overtake the US and turn into the next hegemonic superpower, politically and economically. Certain activities speak of concrete efforts towards expanding influence. The country’s flagship project, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), aims to boost China’s position in global trade by way of developing a “New Silk Road”. The project connects the People’s Republic with more than 60 countries in Africa, Asia and Europe harking back to the old Silk Roads connecting Asia, Africa and Europe in the first century AD.

With a total volume of US$4-8 trillion, China invests heavily in the modernization and construction of new airports, harbours, highways and railway systems in various countries along the routes, which are crucial for the transportation network. Critics have pointed out that China offers loans that are much more flexible and with less red tape to countries which are renowned for their corruption-scandals and anti-democratic institutions such as Belarus and Azerbaijan.

Apart from concerns related to democratic governance, advancing the New Silk Road is likely to produce conflicts within the European Union. Italy recently joined the BRI, after being pressured by consolidation-policies demanded by Brussels. Signing a deal for 29 projects (€2.5bn) with Chinese President Xi Jinping, Italy’s strategy may add momentum to centrifugal tendencies within the EU.

Thus in order to cope with political challenges China has started to build a second network dedicated to building the political infrastructure to champion the New Silk Road. Apart from support from private companies such as Huawei and lobby-groups such as ChinaEU, think tanks and think tank networks come to play an important role in promoting the project. The lobby watchdog organisation Corporate European Observatory (CEO) has recently published a timely report on “China’s growing trail of think tanks and lobbyists in Europe”.

Think tanks such as the Foundation France-Chine or the Brussels Academy for China and European Studies receive funding by the Chinese government. The well-known Friends of Europe organisation hosts the annual Europe-China Forum. In addition to individual think tanks, two international think-tank networks have been established for the promotion of the Belt and Road Initiative, according to the CEO report: The Silk Road Think Tank Network (SiLKS) and the 16+1 Think Tank Network.

SiLKS was established in 2015 and consists of around 40 think tanks. Among its members are prominent think tanks such as the UK based Chatham House or the German Development Institute. The map below shows all member organisations of SiLKs and their locations.

In contrast to the broad geographical spread of SiLKS, the 16+1 think tank network was created to specifically focus on the relation between China and Central and Eastern European Countries. Member think tanks produce reports on obstacles and investment opportunities for China in Eastern Europe. They also function as connection hubs between high-ranking Chinese officials and Chinese companies with politicians and diplomats from the 16 Eastern Europe and the West Balkan countries. This region is of particular interest to China and given the tensions within the EU it will be interesting to see if and how growing Chinese influence interferes with EU ambitions for unity. In any case, the work of think tanks and think tank networks remains high on the Chinese agenda, considering the top level support from the Chinese Communist party leadership.

The Chinese government’s actions to create the political structures in support of the New Silk Road through political consulting and lobbying reflect the critical role ideas and ideological support play. The parallel and interconnected evolution of China’s economic prowess can be observed in its infrastructure projects and ideational coalitions. At the same time, recent Chinese strategies replicate longstanding relations of Western powers, matching European and American foundations and think tanks such as the Adenauer Foundation or Aspen Institutes that have established a presence around the world after WW II: In a “battle of ideas“, as the Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci termed it, (organic) intellectuals are crucial for the provision of ideological ammunition to sort out conflicts, to organize consent and to legitimize political dominance. Think tanks provide the most ideal organizational format for such tasks, as they can be used for many different purposes from organizing public conferences and closed door meetings, producing policy reports and recommendation to gaining media attention and, last but not least, facilitating all kinds of encounters and exchanges between the State and private interests. Studying the activities and the connections between think-tank can help us gain a better understanding of the role that ideational and material factors in international struggles over economic and political power.